Execution in the IEHIAS

- The text on this page is taken from an equivalent page of the IEHIAS-project.

The execution stage is the heart of the assessment process; it is the point at which the full analysis is carried out and the results obtained.

The steps involved may vary, depending on the nature of the issue, the scenarios and the type of assessment. In broad terms, however, the process follows the causal chain. It thus comprises four main steps:

- Estimating exposures of the target population to the hazards of concern

- Selecting an appropriate exposure-response function

- Quantifying the health effects

- Aggregating the health effects into a set of synoptic indicators of impact

Because assessments involve a comparison between two or more scenarios, however, each of these steps has to be repeated, for each of the scenarios. Ensuring that this process is done consistently is crucial, for otherwise biases in the results are likely to occur. It is therefore essential that the assessment protocol is carefully and closely followed throughout the execution phase.

Contents

Managing the assessment

If the previous steps of issue framing and design have been properly done, and the assessment protocol is carefully followed, the execution phase ought to be relatively straightforward, and generate few surpises. A number of difficulties and dangers may nevertheless arise. A large and varied team of people may, for example, be involved in doing the assessment, and it can be difficult to ensure that these work together and retain a clear and common view of the agreed principles and goals.

Partly for this reason - but also because of the inevitable pull of individual interest and the push of the available data and models - assessments may drift from their original purpose, so that in the end they no longer satisfy user needs.

In addition, uncertainties may grow, unseen, as the analysis proceeds to the point where the results become of little value.

In order to safeguard against these, a number of cross-cutting actions are essential throughout the execution phase:

- Procedures and facilities for effective collaboration within the assessment team need to be maintained, for example via a collective on-line workspace and regular meetings, while wider liaison needs to be maintained with the stakeholders;

- Strict procedures for documentation and tracking need to be enforced, to ensure that a full audit trail is maintained for the assessment, and is available for scrutiny at the end of the study;

- A rigorous system of data management and quality assurance needs to be in place, to ensure that all data and methods are valid, and that the results make sense;

- A continuous process of uncertainty monitoring and evaluation needs to be maintained, to give early warning of problems, and to enable corrective measures to be taken before uncertainties become excessive;

- Repeated referral needs to be made to previous studies, to give reminders about unforeseen problems and to help avoid unnecessary duplication of work;

- Methods are needed to assess the performance of the assessment, both in terms of meeting its objectives and its scientific credibility.

Collaborating on an assessment

One of the main challenges in undertaking an integrated environmental health impact assessment is to arrange and organise the collaboration that is needed across what is often a large and varied assessment team. The difficulties are often made all the greater by the different disciplines and levels of expertise of the participants, their geographic scatter across different areas, and the simple limitations of time and other resources. There is also an obligation to restrict the volume of travel, in order to minimise impacts on the environment.

Given these constraints, collaboration inevitably relies increasingly on the use of the Internet, not only for email contact and exchange of data etc, but also for interactive discussion, modelling and development of reports. To facilitate these activities, a number of more-or-less standard procedures have evolved, including the use of a central, co-ordinating website, a document management system and clear reporting systems. In most cases, however, it is likely to be beneficial to go beyond these, and to establish of some form of collaborative workspace. If the concept of open assessment is followed, this will provide an environment not only for centrally-organised collaboration but also for more informal and organic activities - e.g. self-organised groups and ad hoc consultations on specific issues. A leading example of this is provided by Opasnet.

Liaising with stakeholders

In the early stages of an integrated impact assessment, stakeholders play a crucial, and often leading, role in helping to frame the issue and shape the assessment (e.g. by helping to define relevant sacenarios and identify key indicators). The execution stage, by contrast, tends to be a more technical phase, and is therefore dominated by the scientists involved. Stakeholders, however, should not be left on the sidelines at this stage, for they have an important part to play:

- in overseeing the assessment and ensuring that it stays faithful to the original intention and principles;

- in agreeing changes to the study protocol where these become necessary or expedient;

- in contributing directly to the science, where their experience is relevant - e.g. in selecting weights for indicators of social preference.

Continued liaison with stakeholders thus needs to be maintained during the execution phase. This implies arrangements not only for regular meetings or remote (e.g. on-line) consultations stakeholders, but also the preparation and production of relevant summary reports on the work to date and the interim results. Achieving this with a large body of stakeholders can, of course, be difficult and time-consuming, and may delay the analysis. In many cases, therefore, it is more effective to establish a smaller group of representatives, with the time and expertise necessary, to act on behalf of the wider body of stakeholders during the execution phase - for example, in the form of an oversight group or stakeholder partnership.

Participating in assessment

Assessments and participation

Integrated environmental health impact assessment (IEHIA) is an endeavour of analysing relations between environmental phenomena and human health for the purpose of informing decision making about actions to reduce adverse health effects and enhance beneficial effects. It is, by its nature, a multi-disciplinary endeavour that addresses issues of potential interest to a great number of people with different kinds of perspectives: not just scientific experts appointed to the task and policy makers with an obligation to deal with the issue, but also representatives of industry and commerce, NGOs and the general public, amongst others. IEHIA can be perceived as a science-based activity taking place at the interface between science and society, and with the intention both of achieving good governance, and - to this end - strengthening enlightenment and awareness among members of society at large.

It has long been recognised that assessment, in almost any area, needs and benefits from interaction with stakeholders. In part, motivation for this view has come from developments in participatory governance, such as the Aarhus Convention, aimed at at access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice in environmental matters (UNECE 1998) . Partly, too, it derives from the needs of assessors to improve the effectiveness of their assessments, especially in terms of relevance, acceptability and information quality. However, far too often the assessment practice still remains closed: contacts with users is kept to a minimum, collaboration within the community of experts is rare, and participation is allowed only when required by regulation. Even in processes where participation has become common practice, it is often seen more as an additional burden than a substantive part of the assessment or decision making process (Inkinen 2007, Simila et al. 2008). The old tradition of separating science-based knowledge creation from its use still lives strong in the assessment communities. At the same time, however, development of the web has revolutionised the possibilities for collaboration, and greatly raised public expectations for involvement.

Participation practices have already been developed for and widely applied in IEHIA related assessment and decision making processes. There are some problems, however. Firstly, most participatory approaches consider participation as a part of decision making, not so much as a part of producing the information basis for decisions. Secondly, the prevailing assessment processes are designed as closed processes by default and the participatory aspects are mostly considered as add-on modules that bring only local or provisional moments of openness, or semi-openness, to these processes. If the ideals of participation are to be fulfilled in IEHIA, the assessment procedures must be designed so that participation is included as an intrinsic property of the whole assessment process itself. Consequently, the participants should be brought as an essential part of the assessment process.

This perspective assimilates participation with social learning by collective knowledge creation, where the participants, together with assessors and decision makers, learn about the issues at hand by collaboratively engaging in finding answers to the questions in consideration. Participants’ learning is seen as an important outcome of the assessment in addition to the primary objectives of producing an assessment report and influencing the decision where the information is used. This is in accordance with the direct participation theory of democracy. Collective knowledge creation among decision makers, assessors and other participants, is also a major vehicle in improving the outcomes in terms of the primary objectives, the assessment product and its use.

Reasons for participation

"History shows us that the common man is a better judge of his own needs in the long run than any cult of experts."

The reasons for citizen participation have been identified by Fiorino as substantive, normative or instrumental. Another classification of reasons for participation is given by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean as ethical, political, pragmatic or epistemological. Making a fusion of these classifications, the reasoning behind stakeholder involvement is discussed below under four headings as follows:

- Normative and ethical reasons

- Instrumental, pragmatic reasons

- Epistemological, substantive reasons

- Political reasons

Fulfilling the normative requirements and addressing ethical concerns sets the minimum level for participation in IEHIA. In many cases there are regulations concerning the rights of stakeholders or citizens to participate in the societal decision making processes and thereby to also provide their input to the assessment processes. Public hearings at different stages of environmental impact assessment processes e.g. on major energy production site plans is an example of this. From an ethical perspective the scope of participation should extend at least to those whose well-being is or might be affected. Of course determining who is or who is not affected by something can be very difficult, so this type of reasoning can only be considered as a guideline, rather than a rule. According to this reasoning, the perspective to participation is: "who and how do we have to include in the assessment?".

The instrumental, pragmatic reasons relate to improving the outcome of the assessment by means of participation. This could be accomplished e.g. by increasing the sense of ownership, trust and acceptance of the assessment among those who are invited to participate. Also improved relevance of the assessment through inclusion of multiple views and perceptions can be sought for by participation. A related example would be inviting local people nearby a planned waste incineration site to express their concerns early on in the assessment process, and address those concerns in the assessment. Although all the locals may not be happy with the outcome, they are more likely to accept it if their concerns were given a fair treatment and well-founded answers to their questions were provided within the assessment. Following this reasoning, the perspective to participation is: "whose concerns should we include in the assessment, if we want things to go smoothly?".

Probably the greatest potential of benefiting from participation lies in making use of the diverse knowledge and plurality of views among stakeholders and public. Stakeholders may possess some local or other special knowledge about the phenomena being assessed that is not held by experts or that is not available in any official databases or information sources. Perhaps even more importantly, stakeholders and citizens are the best representatives of their values and are thus a crucial source to be included in IEHIA and other assessments that often deal with controversial issues. Non-experts see problems, issues, and solutions that experts miss. Participation can be seen as a means to improve the actual content of the assessment by bringing in knowledge and values of the stakeholders or public. The perspective to participation in this reasoning is: "who could know something that we would not otherwise obtain, and how to incorporate that into the assessment?".

Political reasons relate to the basic ideas of democracy. The society must have control over issues that have impacts on the well-being of of the society and its members, i.e. the government should obtain the consent of the governed. Whether approaching the issue of participation from the point of view of pluralism (polyarchy, interest group liberalism) or direct participation, it is essential for the democratic system itself to incorporate possibilities for participation. Actually, this kind of reasoning forms the background for other above mentioned reasons as it points out that participation is necessary if a society were to be democratic rather than technocratic. Following this reasoning, the perspective to participation becomes: "is it fair not to let interested people have influence on the outcomes that affect them?".

All in all, the reasoning behind participation is basically quite practical: to come up with better assessments and consequently better decisions, actions and consequences. Collection and synthesis of the knowledge and views of a diverse group of people tends to lead to better outputs than just relying on the knowledge and views of only few individuals, even if they were experts. Also, inclusion of diverse groups to contribute to the work tends to increase the acceptability of the outputs and can help to improve the usability of the outputs. Even the efficiency of the assessment process can be enhanced by participation, although badly designed and managed participatory practices can also turn out counterproductive in this sense. More inclusive procedures enrich the generation of options and perspectives, and are therefore more responsive to the complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity of the risk phenomena and more intensive stakeholder processes tends to result in higher-quality decisions.

Participation and openness

Basically, participation in IEHIA means allowing non-experts to join the information production process by sharing their knowledge, providing questions, and expressing their values. If all the reasons for participation are considered, the purpose of participation is to improve both the substance and functionality of the assessment output, not just to fulfill an obligation. Also, it should not be only a one-way process of informing participants, neither merely drawing information from participants. The overall outcome of the assessment and/or decision making process is the main goal, but also social learning, particularly in the direct participation view to democracy, is important. In a dynamic two-way participatory process the participants both contribute to the assessment and learn as a part of the process. In fact many of the desired outcomes underlying the reasons for participation can be seen rather as results of societal learning than intrinsic properties of the assessment product.

In a dynamic two-way process, where participants have an active role, it is not meaningfully possible to keep the assessment process closed to experts, and perhaps decision makers, only. Thereby, the concept of openness becomes a central issue in participatory IEHIA. Openness considers the ways how interaction between assessors, decision makers, and other participants can be organized and managed. Some important aspects of openness can be identified as follows:

- Scope of participation

- Access to information

- Scope of contribution

- Impact of contribution

- Timing of openness

Scope of participation refers to who, and on what basis, are allowed (or inversely not allowed) to participate in the assessment. Access to information refers to which parts of assessment information are set available to participants. Scope of contribution refers to which aspects of the assessment are different participants' contributions invited and allowed to. Impact of contribution refers to what extent may a particular contribution have influence on the assessment and its outcomes, i.e. how much weight is given to participants' contributions. Timing of openness refers to when, e.g. in which phases of assessment, are participants' contributions invited or allowed. The overall openness of an IEHIA process can be considered as a function of all different aspects of openness.

The degree of openness can be managed in terms of the above-mentioned aspects in relation to the purpose and goals of the assessment, taking into account the situational, contextual, and practical issues, e.g. legal requirements, public perceptions, available resources, time constraints, complexity of the case etc. The degree of openness can also be adjusted separately for different groups of participants as needed and the degree of openness may vary from assessment to another. The default in participatory IEHIA should, however, be complete openness, unless otherwise can be well argued. In open participation anyone is allowed to raise any points related to an assessment at any point during the making of the assessment. Any limitation of openness, in terms of any aspect of openness, must always be well defended. This is quite contrary to the current perception, where the default tends to be a closed process, and deviations towards openness require reasoning.

Challenges of participation

Unfortunately the benefits of participation are no achievable without some costs. Opening the assessment processes for participation brings about new challenges for IEHIA. Correspondingly, the methods and tools for IEHIA need to be designed in a way that these challenges can be overcome. Still, however, perhaps the biggest challenge lies in changing the mindset and attitudes of assessors and decision makers to perceive participation as an enhancement to assessment practices, not as a burden. Some of the most obvious challenges to IEHIA brought about by participation, along with some brief explanation, are discussed below. Some more consideration on tackling these challenges is provided also in the chapter on facilitating participation.

Quality of non-expert contributions

An often heard argument for closed assessment processes is that non-experts do not have enough knowledge to make sensible or relevant contributions. As a consequence it is considered that their involvement is either futile or even harmful. This thinking, however, highly overvalues experts' capabilities. For example, in the context of environmental health, most problems are so broad and multi-faceted, that even the greatest environmental health expert of all ends up being a non-experts in relation to many aspects of the problem. Also, IEHIA considers issues where natural and societal phenomena are multiply intertwined, and often involve aspects about which the lay-members of the society themselves are the best experts. After all, some of the main benefits that are sought for by participation do come from expanding the information input to the assessment to cover issues that could not be obtained from experts, databases, scientific journals and other common information sources of scientific studies. The assessment processes need to be designed and managed in a way that the participants have a meaningful role in the process and that their information input is dealt with in a useful way. Also the methods and tools for collecting, synthesizing and communicating assessment information must be designed so that the plurality of sources and types of information included in the assessment can be dealt with.

Inclusion of values and perceptions in a scientific assessment process, not only decision making process

Most participation approaches consider participation as a part of the decision making process, not the assessment process. Similarly, it is often considered that the values and perceptions of stakeholders or public only have a role in the decision making process, not the "scientific and objective" assessment process. However, if the input to the decision making process is desired, it should be included already in the assessment that the decision making is based on. How else could the input be systematically incorporated into the overall process of assessment and decision making? This input includes participant value expressions and perceptions as well. Although the old idealistic view of a value-free and objective scientific assessment strictly separated from the value-laden, political decision making process still lives strong in many people's heads, that view is disingenuous. The values of assessors inherently guide the assessment towards certain directions, even if they were left implicit, unanalyzed and hidden under a facade of scientific objectivity. Clearly, broadening the value base and making its analysis and impacts to the assessment explicit is a more defensible option. The participant input, including both knowledge and values, should, and can, be incorporated already into the assessment. Value statements are in many ways similar to other kinds of information, e.g. observation data, and there are no fundamental reasons why value statements could not be analyzed systematically in assessment.

Dealing with disputes

In participatory assessments on controversial and important issues it is likely that there are no obvious, definite and generally accepted answers to many questions. For example, values might be in dispute, evidence may not be decisive, or there may be lack of agreement on understanding how a problem is to be addressed. Anyhow, the probable emergence of disputes in participation should not be considered as a problem, but a possibility. Disputes tend to point out weaknesses in the assessment and addressing them in a proper manner is likely to make the assessment better. Also, disputes are useful from the social learning point of view, as they trigger discourses that can lead e.g. to broadening of perspective, correction of false assumptions, and enhanced understanding upon the assessed issues among both external participants and assessors as well as decision makers. Again, the assessment processes, methods and tools need to be designed in a way that they can accommodate and facilitate constructive deliberation upon the issues in dispute.

Protecting from intentional jamming and delaying of assessment by junk contributions

Sometimes possibilities of participation are considered as possibilities of hampering on-going processes of assessment or decision making. This could mean e.g. dissemination of disinformation, formulating repeated appeals on minor issues in a formal process, or just flooding the process with an overwhelming flow of junk contributions. This is a reasonable threat, but it is actually more relevant in cases of closed processes with no explicit or fair treatment of outsider contributions. If participation is organized so that it is open, meaningful, effective and fair, many of the reasons to take such extreme actions to hamper the process are lost. It is still necessary to guarantee that the methods of participation can deal effectively, but fairly, with irrelevant, ungrounded, or even hostile contributions.

Low willingness to participate

Often the discussions on participation consider how to allow or enable participation, but common is also the case that it is difficult to find people willing to participate. The fact that often people do not want to participate does not, however, overrule the fact that possibilities for participation should be increased. In some cases the willingness may well be a result of distrust in the system and doubts upon the effectiveness of participation. Low willingness to participate might be a symptom of dysfunctional participatory practices, rather than disinterest in the issues assessed or decided upon. For example, based on three case studies from different continents, Fraser and co-workers concluded that the process of engaging people provides an opportunity for community empowerment; that stakeholders and decision-makers consider participation irrelevant unless it formally feeds into decision-making. In addition to being meaningful, participation should be made as smooth and effective as possible. In some cases it might also be necessary to come up with means to motivate certain important stakeholder or citizen groups to participate in order to guarantee a broad enough representation of perspectives to be included in an assessment.

Cost and time expenditure of participation

Organizing broad participation that has substantial impact on the assessment requires expertise, takes time and effort, and is costly. This is true in many traditional ways of organizing public participation and stakeholder involvement. However, these methods do not make much use of the possibilities provided by modern information and communication technology. Face-to-face meetings, group negotiations, public surveys, public hearings etc. all have their strengths in organizing participation, but a big part of the potential outcomes that can be expected to be achieved by these methods, could also be achieved in virtual settings. Moving into web-workspace-based participation also enables much broader participation without the need to limited in terms of time and space. Also the costs of virtual participation are in most cases much smaller and it can allow more speed and transparency to the process. The traditional participatory efforts can be focused in cases where physical contact is considered necessary and complemented and supported with the means of virtual participation possibilities.

Assessors' and decision makers' attitudes towards participation

The last, but not least, challenge is the attitudes of the people who are in charge of assessments and decision making processes; assessors themselves and decision makers as users of the assessments. The prevailing assessment tradition is that assessments are closed processes, and participation by non-experts is seen as a threat to the quality and objectivity of the assessment. Most of the current methods, tools and practices have also been developed according to this mindset. Despite a whole lot of studies that indicate a need to move towards more open participation as well as encouraging examples from other fields, participation is still often considered as an annoyance or even a burden. Could IEHIA, as a new integrated approach to environment and health assessment, be a pioneer in this sense, and take also the task of integrating people and perspectives as a part of its mission?

Facilitation of participation

Facilitation of participation is about methods and tools that provide the means to enable participation. Methods are the means to achieving the goals of the assessment and tools are the means to applying the methods as intended. The methods and tools to facilitate participation should not be considered as separate methods and tools for participation in addition to the methods and tools for assessment, but rather as the participatory functionalities of the assessment methods and tools. As stated above, participation should be integrated into the assessment process itself, not treated as a separate add-on process alongside or, as sometimes happens, after the assessment.

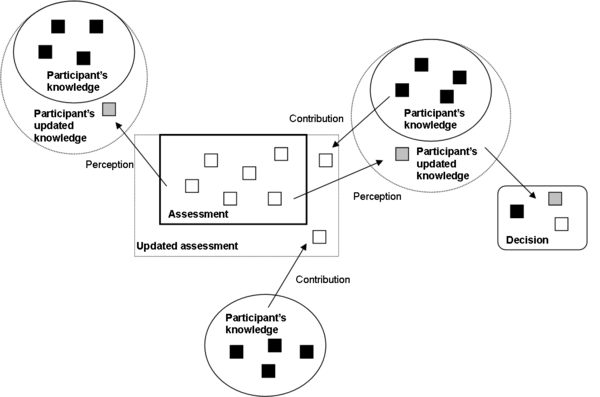

What basically is required in enabling participation in assessments is to make the participants become a part of the assessment process by:

- Providing participants possibilities to get acquainted with the assessment

- Providing participants possibilities to contribute to the assessment

- Synthesizing participant contributions into the assessment

- Explicating the impacts of the participant contributions to the assessment

- Providing possibilities to do it all again in repetitive iterations

Although the point of view above is that of an individual, it should be realized that when considering participation as an activity of a collective, it is a compilation of multiple, overlapping individual processes taking place simultaneously.

The first bullet actually comprises of two different factors, the availability of information and usability (or comprehensibility) of information. The participants need to have access to the information in a suitable media when it is needed, but they also need to be able to understand, or internalize, the information. This must, and can, be facilitated by assessment methods and tools. It must be noted that both factors, but in particular usability, are also determined by the capabilities and other properties of participants themselves, and education and other modes of participant support may also be needed.

Equipped, ideally, with adequate acquaintance with the issues of assessment, the participants are most often likely to identify points where their perceptions, values, and understanding of the issues do not match with what is currently represented in the assessment. Things may be missing or they may be in conflict. The methods and tools must provide support for identification of these points as well as formulation and externalization of the statements regarding these points.

Perhaps one of the most challenging things in enabling participation, but also in knowledge creation at large, is the synthesis of contributions into existing body of knowledge. The whole activity of information collection from participants is futile unless their contributions become incorporated into the assessment.

If the participant contributions are duly synthesized in the assessment, they also have corresponding impacts on the assessment outcome. The impact still needs to be clearly explicated for two reasons. Firstly, in a collaborative process, the contributions and their impacts must be made explicitly available as a part of the shared information to other contributors, so that they can, in turn, internalize them as parts of their participatory actions. Secondly, as mentioned above, the participants will consider participation as irrelevant, unless they see that their contributions have a real impact on the outcome. Again, this is not only a question about the interaction between the participants and the assessment, but also about the interaction between the assessment and its use, and what role do the decision makers, as the users, give for the assessment in their decision making process.

Methods for facilitating participation

The methods for participation can be considered in terms of two categories according to their perspective to the issue of participation. The first category is methods for collective knowledge creation, considering the issue from the point of view of developing the shared information object in collaboration. The second category is methods for arranging events of participation, focusing on the participatory procedures. These two categories are briefly described below.

For a major part the basis for enabling participation in assessment is determined by the ways that question generation, information collection, hypothesis creation and development, information representation, and interaction among contributors is organized and supported. By contributors we mean the whole collective of assessors, decision makers (problem owners), and external participants that jointly contribute to a particular assessment. To date the methods of collaborative knowledge creation are more in the form of theoretical principles of applied epistemology rather than practical guidelines. Examples of theories relevant to collective knowledge creation in assessment are interrogative model of inquiry (I-model), trialogical approach, hypothetico-deductive method, abductive reasoning, Bayesian inference, and pragma-dialectical argumentation.

How, when, where etc. to organize participation is naturally more or less affected by the choices regarding the degree of openness in its different aspects in particular assessments. The procedural methods for participation are various and designed for different needs and different contexts. Despite some considerations on suitability of different approaches for different types of situations and problems, the method descriptions tend to be focused on managing the participatory process, and remain vague on incorporating participant contributions to the assessment.

Tools for facilitating participation

The role of tools in facilitating participation is in aiding the participatory use of chosen assessment methods while striving for the goals of the assessment. Here we consider facilitation in the case of unlimited participation, as it includes and exceeds all forms of more limited participation. We also focus on facilitation in virtual settings where participation is supported by or takes place over information networks, to a greater or lesser extent. This perspective does not rule out, but rather complements or reorganizes the more traditional approaches to participation.

The requirements for participatory tools can also be considered as comprising of two categories, those of facilitating the activities of an individual, and those of integrating the individual activities as collaboration. All in all, the compilation of such tools constitutes a collaborative assessment workspace.

A collaborative workspace is a virtual working platform that allows open groups to participate in assessments. It is an interface for the users to access the assessment contents, make their contributions to the assessment and communicate between each other. It also provides tools to organize and manage the user contributions. In fact the collaborative workspace is a virtual location of storing, manipulating and representing information. It enables the participants to communicate with each other in the form of making their contributions to the contents of the assessment. Enabling this communication through contribution is the primary function that the collaborative workspace provides. Enabling this also includes managing openness, both according to individual users and user groups or according to locations within the information structure of the content. Furthermore, the collaborative workspace provides users with access to specific tools that they can use for making their contributions. Basically the idea behind the workspace is that everything can be searched for, found, saved, exchanged and discussed about in one place. In other words: The workspace functions as the "glue" between all parts of the assessment, helping the assessors to keep it together and in order, as well as enhancing both efficiency and effectiveness of assessments.

In order to be functional, the collaborative workspace should provide its users with:

- access to browse, search, read and use the information contents of the assessment

- access to use specific tools to analyze and explore assessment information

- possibility to contribute to the assessment

In the case of an individual user, satisfying these requirements is technically quite simple and possible to implement in many different kinds of systems. An example could be a stand-alone content management system in a single computer complemented with access to simulation tools. The actual challenges come from representing information in ways that support participants’ cognitive processes of interpreting and internalizing assessment information as well as externalizing ones contributions as parts of the assessment. Division of assessment information content into manageable and comprehensible pieces by ontological information structure, representation of assessment as causal diagrams, and possibility to play with assessment models are examples of possible facilitating functionalities that a collaborative workspace could host to address these challenges.

In the normal case of multiple participants, the situation becomes more complicated. The individual contributions need to be turned into collaboration. The challenge for the workspace becomes one of synthesizing contributions and managing changes.

In order to make the above mentioned functionalities manageable in situations of multiple participants, the collaborative workspace must also enable:

- version and history control of all individual pieces of information

- management of openness, both according to users and according to content

- management of simultaneous use of tools and simultaneous editing of content

Documentation and auditing

Maintaining an effective and comprehensive audit trail for an integrated impact assessment is vital for a number of reasons:

- The process of doing an assessment is often complicated, involves many different individuals, and may include a number of false turns and adjustments; to ensure that the process does not become chaotic, it is essential that every step is properly recorded, and justification for every decision can be reviewed if necessary.

- Integrated assessments often have far-reaching implications for policy-makers and other users. If they are to be convinced that the results are valid and merit a response, then they need to be able to scrutinise the procedures used in the assessment, and satisfy themselves that the decisions taken in the process were valid.

- Experience in doing integrated assessments is scarce, and we can all learn from what others have done; providing access to clear documentation about what was done, and to details explaining the rationale, helps others learn good practice in integrated assessment.

Specific standards and tools for documentation of integrated assessments have not been established, and the methods used need to be developed to work within the context of the assessment and organisations involved. Useful ways of ensuring effective documentation, however, include:

- Annotating the assessment protocol (in the form of cross-referenced annexes and supplements) to provide specific detail on the decisions or changes in approach made during the process, and the methods used at each step in the analysis;

- Supplementing the assessment protocol with a clear critical path diagram, and annotating this to record key decisions, methods and outcomes;

- Maintaining a rigorous 'versioning' procedure (including naming and archiving) for all elements of the assessment (e.g. conceptual models, data files, analytical models, results) so that the steps involved in reaching the final outputs of the assessent can always be retraced;

- Developing comprehensive metadata for all derived materials (including both intermediate and final results), which dscribe the procedures used to generate the information.

Data management

Managing the wide range of data that are used in, and produced by, an integrated assessment can pose a serious challenge. The problem is not only to record carefully what data are used and generated, in order to monitor the progress of the assessment and provide a detailed audit trail, but also to ensure fitness for purpose - that the data and results are able to do the job for which they are needed. This is especially important because, during the course of an assessment, data may be fed through a series of different but linked models, and end up far from their original position or purpose. This inevitably raises dangers that data will be inappropriately used, and that the results will thus be flawed.

An effective system for data management and quality assurance is therefore vital. To be effective, this will comprise four key elements:

1. Data standards (developed at the Design stage):

- A clear set of criteria specifying minimal requirements for data inclusion or data linkage;

- A clear set of tolerances, identifying the limits of uncertainty for the results - and thus the threshold for exclusion.

2. Testing and validation

- Carefully specified requirements and procedures for testing and validation of data and results - both to ensure that they meet the relevant data standards and that inherent uncertainties are evaluated and reported;

- A series of approved reference data that can be used to test and validate models under controlled conditions.

3. Metadata (information about the data)

- A rigorous and consistent procedure for recording metadata (including a Glossary of terms and definitions);

- An up-to-date and searchable data catalogue, containing all the metadata records;

- A feedback system, facilitating the reporting of newly discovered problems or issues with the data sets (whether by members of the assessment team or external users).

4. Tracking and alert

- A quick and effective system for tracking who is using which data, as part of the assessment;

- A clear and simple system for reporting on any changes to current data sets, or any newly discovered data problems, to other members of the assessment team.

Managing uncertainties

The lengthy and sequential analysis involved in many integrated impact assessments gives opportunity for uncertainties to develop and grow. If unchecked, these can in some cases build to a level where they swamp the results, making them of little practical value. At the very least this implies a wastage of effort in completing the assessment; at worst, it can lead to poor decision-making and ineffective or even harmful action.

It is therefore essential not only to identify and categorise potential uncertainties at the design stage of an assessment (see link to Characterising uncertainties, below), but also to evaluate and track them as the assessment proceeds - and if appropriate to compare them with a specified limit for uncertainty for the final results. When large, or unexpected uncertainties are dentified, their cause needs to be investigated, and in most cases some frm of remedial action (e.g. use of better data or a different model) taken. However, it is not always appropriate immediately to terminate the assessment if the uncertainty limit is exceeded, for in some cases uncertainties may cancel out! At least some degree of tolerance might thus need to be applied. In addition, even very uncertain assessments can be informative, if only in showing where further monitoring or research needs to be done.

Monitoring uncertainties in the assessment

Identifying uncertainties is not always easy. Nevertheless, in well designed integrated impact assessments it is at least facilitated by basing assessment on a clear and detailed conceptual model of the system being studied, and by following the causal chain. In this way, clear expectations about the results can be built up, and the results viewed and evaluated at various intermediate stages in the assessment.

In an ideal world, uncertainties at these intermediate stages in the analysis can be evaluated by comparing the results with independent reference data. Thus, estimated pollutant concentrations can be compared with current, monitored concentrations to determine whether they show a consistent distribution and lie within a plausible range. Similarly estimated exposures can be compared with survey data, from analogous situations, and excess risks can be checked against those found in previous studies. A range of statistical analyses are available for this purpose (see link to Methods for uncertainty analysis, below).

In many instances, however, external validation of the results in these ways is not possible, simply because relevant data from matching situations do not exist. In these cases, uncertainties may only be spotted by comparing against prior expectations of what the results should look like at key stages in the analysis. Wherever possible, these expectations should have been specified in advance (e.g. during the Design phase) - for example, as an anticipated distribution or range of likely values, and/or as a direction of effect (e.g. expected direction of change in the outcome variable from one scenario to another). Another useful tool is sensitivity analysis: rerunning specific elements of the assessment with changed input variables (or different models) to determine how robust the results are to small differences in the analytical conditions.

Where even this is not possible, then a more subjective estimate of uncertainty needs to be given based on the general credibility of the preceding data and methods that have led to the result at that stage. One useful approach in these situations is to use an uncertainty scorecard. This should be designed to indicate the sources and levels of uncertainty at each stage (location) in the causal chain, and show (in at least a qualitative way) how these accumulate as the analysis proceeds (see link to Methods of uncertainty analysis, below). To set the uncertainty estimates into broader context, a useful trick is finally to compare the overall level of uncertainty with that associated with other, better known risks (e.g. smoking and lung cancer, or solar radiation and skin cancer), for this gives the tlimate user a yardstick against which to make judgements.

Assessment performance

Introduction

Environmental health assessments are endeavors of producing science-based support to societal decision making upon issues related to environment and health. They produce information for specific needs thus making the information objects produced in assessments intentional artifacts; means to ends. There are two common views to assessment performance. The uncertainty approach focuses on the intrinsic properties of the information produced in assessment. The quality assurance/quality control approach focuses on the process of producing that information. However, in order to capture all factors that contribute to the overall assessment performance, it is necessary to consider not only both the production process and the information produced, but also the process of using that information. The properties of good assessment consider assessment performance as a function of (i) the quality of information content (ii) applicability of information, and (iii) the efficiency of the assessment process. These property categories are further broken down into eight individual properties that jointly contribute to overall assessment performance: informativeness, calibration, relevance, pertinence, availability, usability, acceptability, intra-assessment efficiency, and inter-assessment efficiency. As such, the properties of good assessment simultaneously address features of: (a) production of information, (b) the information content, (c) the information product, (d) information in use, and (e) characteristics of use context. The properties of good assessment can be used in ex-post evaluation of assessments, but it is most useful in ex ante evaluation during the design and execution phases of assessments.

Performance of assessment

The fundamental purpose of assessment is to improve societal decision making. Assessment should thus provide relevant information about the situation that the decision making is about, most often preferably in a quantitative form if possible. In general the information is useful to be formulated as predictions on the impacts of possible decision options on certain outcomes that are of societal importance. All assessments should always be done according to a specified information need in a decision making situation. When the purpose is identified and kept clear in mind and preferably publicly explicated, it helps to guide the assessment process in producing a desired kind of assessment product that helps in making good decisions. Explicit definition of the assessment purpose, preferably early on in the process, is an essential and integral part of assessments.

The overall purpose of risk assessment can be considered as composing of two different aspects. The general purpose is to describe reality, i.e. to explicate real-world phenomena in a comprehensible and usable form. But mere describing reality without any specific, identified need for the description would probably not make much sense as such. There must also be a certain specific purpose to undertake such a task, an instrumental purpose, or use purpose, for the output of the assessment. For each particular assessment, the specific situation, and thereby the instrumental purpose, is naturally different and thus the outputs of each assessment are and should always be case-specific and in accordance with the contextual setting of the particular case.

The performance, or the goodness, of assessment means how well it fulfills its purpose, or actually its both purposes. Assessments produce pieces of information, artifacts, that are intended for use in a certain setting. The performance of assessment is a property of a piece of information in its use, and derived from its making. As practical means to practical ends, the performance of assessments can be considered according to their instrumental functions:

- functional goal

- use plan

- contexts of use

- artifact type

In the context of environmental health assessment, all of these instrumental functions can be determined to some extent. he functional goal is to improve societal decision making, the artifact type is an assessment report, i.e. a description of a piece of reality, the context of use and use plan are often such that policy makers read the report and decide upon something according to the understanding they developed by internalizing the assessment information. I every single case, the situation is however somewhat special, and accordingly the instrumental functions to meet the needs are somewhat different. It can also be questioned whether the normal situations and conditions are such that they optimally promote fulfilling the purposes of assessment.

Approaches to assessment performance

There are two commonly applied approaches to assessment performance that can be referred to as 1) the quality assurance/quality control (QA/QC) approach, and 2) the uncertainty approach. This is a rough, but practical, simplification, and both of these typifications consist of several varying sub-approaches.

The QA/QC approach focuses on the procedure of making the assessment. To put it very briefly, it uses a well-defined procedure as a proxy for good quality of the outcome of the process. Another example of somewhat similar thinking is present in the ranking of different study types and the weight of evidence they produce, and usually concluding that randomized clinical trials produce the best evidence without actually considering what actually is the evidence they produce.

The uncertainty approach focuses on the properties of the assessment product, the piece of information produced in the assessment. The range of different specific approaches to uncertainty is very broad, but they tend to build on the objective properties of the information that are independent from both the making and the use of the information. The basis of the uncertainty approaches is in statistics, but many specific approaches also extend to considering qualitative aspects of uncertainty.

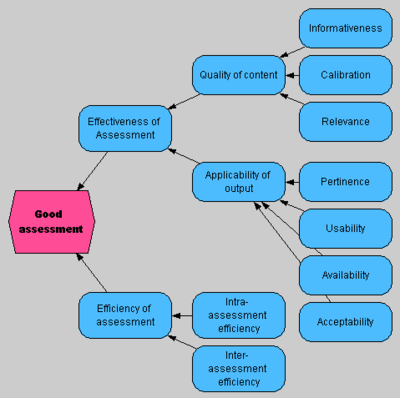

Properties of good assessment

Based on the above considerations, it is possible to define the general properties of good assessment. This approach considers assessments as compounds of sets of questions and hypotheses answers to them. It also addresses not only the assessment product, but also the process of producing it as well as the process of using it. The properties also have their implications that should be taken account of in regard to assessment methodologies. The general properties of good assessments are illustrated as a tree structure in the diagram below. The general goal, good assessment, is the node on the left of the diagram and properties needed to constitute this goal are broken down while moving to right in the diagram.

The properties of good assessment consist of two categories:

- Effectiveness of assessment product, consisting of

-Quality of information content produced in assessment

-Applicability of assessment product

- Efficiency of assessment process

The first two categories, quality of content and applicability of output together form the effectiveness of assessment product. The effectiveness means the potential of assessment to have the intended influence on the decision making processes that the assessment addresses. Effectiveness thus indicates the potential of advancing towards the primary purpose of assessment of improved societal decisions.

Quality of content refers to the goodness of the information content that is produced in the assessment. It consists of three properties: informativeness, calibration and relevance. The point of reference in informativeness and relevance is the reality that is described by the information. The point of reference in relevance is the question that the information is intended to address.

Informativeness can be considered as the tightness of spread in a distribution (All results estimates of variables should be considered as distribution estimates of some form rather than point estimates). The tighter the spread, the smaller the variance and the better the informativeness. Another way to describe informativeness, in particular for qualitative information, is how many different worlds does the information rule out.

Calibration means the correctness or exactness of information, i.e. how close is it to the real phenomenon it describes. Evaluation of calibration can often be complicated in many situations, but it is an important property complementing informativeness. In particular in qualitative terms, informativeness and calibration can be considered as constituting truthlikeness.

Relevance can be described as the coherence of the assessment, i.e. does the assessment address all necessary, and only necessary, aspects of the phenomena being assessed. Relevance is considered in terms of the assessment contents in relation to assessment scope.

Applicability refers to the potential of conveying the information content in the assessment product to its intended use(s). Applicability also consists of three properties: usability, availability and acceptability. Usability and availability are properties of the assessment product that are realized in the process of its use. Acceptability is fundamentally a property of the assessment process, also realized in the process of using the assessment product.

Pertinence means the relevance of the assessment results in relation to the use that they are intended for. It is considered in terms of the assessment scope in relation to the practical need for information.

Usability refers to issues that affect how the user manages to create understanding about the content, such as e.g. clarity of presentation, language used etc. Usability is strongly influenced also by the capabilities and other properties of the users and is often not fully controllable by those who produce the information. Usability can be addresses by explicit definition of the use purpose of the assessment and identifying the intended users and uses.

Availability refers to the openness of access by the intended users to use the assessment product when and where needed. Availability is affected by issues such as e.g. chosen media of representation, and openness of the assessment process.

Acceptability is particularly strongly influenced by the intrinsic properties of the acceptor. Fundamentally it is a question of accepting, or not accepting, the assessment process, how the information in the assessment was come up with.

Whereas the properties constituting effectiveness are primarily related to the assessment product, efficiency is clearly a property of the assessment process. Basically efficiency can be described as the amount of effectiveness (a function of quality of content and applicability) given the effort spent in producing that effectiveness. Efficiency can be considered in terms of a particular assessment or a whole endeavor of assessment practice producing a series of assessments.

Intra-assessment efficiency means the efficiency within a certain assessment, i.e effectiveness of a single assessment over the expenditure of efforts in carrying out that assessment.

Inter-assessment efficiency refers to the reduction rate of the marginal efforts needed for each new assessment with the same quality of output when making a series of assessments. This means in practice the ability to avoid doing the same work again if it has been already done in a previous assessment.

In can be considered that the properties related to quality of content are the most crucial ones. Assuring the goodness of questions and hypotheses as answers to them should thus be the first priority in assessment. Anyhow, the quality of content has most very little significance if the applicability of the assessment remains low. It is therefore also important to explicitly consider all aspects of effectiveness when designing and executing assessments. The importance of efficiency mainly comes from practical limitations and inevitably scarce resources for making assessments. It is necessary to strive for best possible outcomes with the available resources.

The properties of good assessment can be used as a framework for evaluating the performance of assessment. It can be applied in evaluation that takes place as a separate process aside the assessment process, or it can be applied as principles that guide the design and execution of the assessment. The properties of good assessment address the assessment product, but also the process of making it as well as using it. They also address the information produced in the assessment from different perspectives, goodness of questions, answers, rationale, and representation.